In a recent piece published in the WSJ (“Why the Dollar’s Reign Is Near an End“), Berkley Professor Barry Eichengreen declared that the Dollar will soon cease to be the world’s reserve currency. According to Dr. Eichengreen, within 10 years and for various reasons, the Dollar will become one of many reserve currencies, competing for preference with the Euro, Chinese Yuan, Japanese Yen, and Swiss Franc. While Dr. Eichengreen makes some good points, however, I don’t think most of his arguments stand up to scrutiny.

His thesis can be boiled down into a few premises. First of all, he argues that it is fundamentally illogical that oil should be priced in Dollars, and that countries conducting bilateral trade should settle their accounts using Dollars. Dr. Eichengreen is right that this represents the main underpinning of the Dollar. He is wrong to suggest that it will change anytime soon.

That’s because oil ultimately has to be priced in currency. It’s entirely possible that oil exporting countries will band together and decide to price oil in Euros, instead. However, this would mainly be useful as a political tool (albeit a very potent one!) and would serve no economic or risk management purpose whatsoever. If oil were priced in terms of a basket of currencies (such as IMF Special Drawing Rights), it might make oil prices less volatile, but then would require oil exporters to receive 5 (or more!) currencies for their oil instead of one! Finally, the price of oil can and does adjust relative to what happens in forex markets. When the Dollar declined in 2007, oil prices skyrocketed commensurately in order to compensate exporters.

The same largely applies to bilateral trade. While it makes sense for two countries with stable currencies (such as Korea and Japan, for example) to use one of their currencies as the main unit for trade, the same cannot be said for countries with more volatile currencies. For example, if Argentina and Israel are trading, one country would be inherently dissatisfied if trade were denominated either in Shekels of Pesos. When bills are settled in Dollars, however, it is easy and economical for both countries to simply convert those Dollars into currencies which may have more utility for them. As with oil, it’s possible that some countries will decide that it makes more sense to settle trade in Euros instead of Dollars, but again, I don’t see what purpose this would serve and any such decision would probably be politically motivated.

Second, Dr. Eichengreen points out that changes in technology have made it easy to instantly calculate exchange rates and easily convert currency. While I think this point is well-taken, I think people enjoy having a common base currency, if only for psychological reasons. Ultimately, this point is irrelevant because it has very little bearing on the supply and demand for particular currencies.

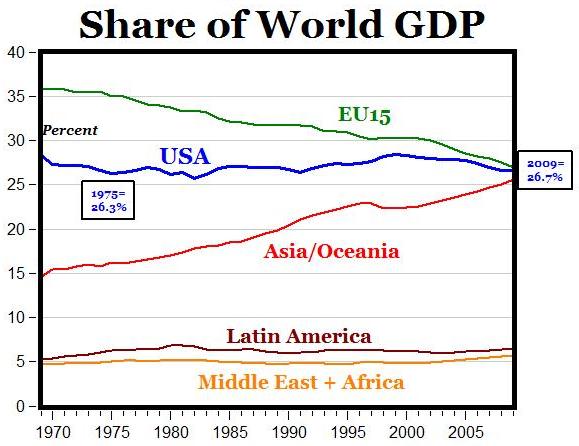

Third, he argues that the Euro and Chinese Yuan both represent latent threats to the Dollar’s preeminence. Again, he’s both right and wrong. The Euro already represents a viable alternative to the Dollar. It’s economy is reasonably strong, its monetary policy is sensible, its capital markets are deep and liquid. On the other hand, it’s being held back by perennial fears about the a Euro breakup, and the fact that the sum of 20 separate parts is not the same as the whole. Since the EU doesn’t issue sovereign debt, risk-averse investors will be limited to buying German/French/etc. bonds, which are always going to be more less liquid and more risky than US Treasury Securities. Besides, you can see from the chart below that the US economy has actually been growing faster than the Eurozone for the last 30 years.

As for China, I expounded in a recent post about how unlikely it is that the Yuan will seriously rival the Dollar anytime soon. While China certainly has plenty of cachet and expanding vehicles for investment, its capital markets remain much too primitive and opaque for Central Banks and risk-averse investors. Most importantly, the structure of China’s economy is such that foreign institutions simply don’t have the opportunity to accumulate Yuan in massive quantities. Simply, the supply is too small. In fact, the Asian Development Bank forecasts that the Yuan will constitute a mere 3-12% of international reserves by 2035. That doesn’t sound very threatening.

Dr. Eichengreen’s final point is that the Dollar’s safe haven status has been compromised. First of all, this is old news. The Yen is already a – if not the – preeminent safe haven currency, thus headlines like “Safe-Haven Yen Gains As Radiation Concern Mounts” that take irony to a whole new level. The same goes for the Swiss Franc. However, any concerns that investors have about the Dollar must necessarily also be projected onto the Yen, Euro, and Pound. All of these currencies face current or looming fiscal crises and slowing economic growth. While investors might diversify into other countries, they’re not going to suddenly dump the Dollar in favor of the Euro.

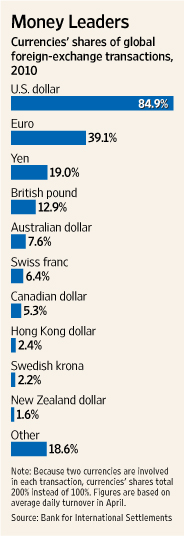

In short, it makes sense that a currency that represents 80% (out of a total of 200%) of all forex transactions and more than 60% of global reserves but only accounts for 25% of GDP, should experience a decline of some sort of decline in popularity. Over the next 50 years, the Dollar will gradually cede share to other currencies. But 10 Years? Give me a break.

0 comments:

Post a Comment